Written by : Eszter BOROS

How can I sum up five months working on youth empowerment in Nishanke, Okhaldhunga?

I simply cannot. A book would not suffice to describe all the adventures, emotional roller coasters, and wonders I experienced. But, for our final presentation, we had to summarise the professional aspect of our time as the youth empowerment team. Three sentences defined our work and summarise my key learnings from this experience:

What to do?

But, in the end, we need money.

We do what we can!

WHAT TO DO?

The first sentence I learnt about working in rural Nepal was ‘What to do?’ This rhetorical question signified two things.

First, it made it clear to me that while in Nepal I should not expect things to work the way they did in my perfectionist, everyday life in Germany. There were obstacles unknown to my European urban life, and I had to accept that many details were out of our control. Yet, plans, processes and projects were carried out. Hardly ever in the ideal way. But with good intentions.

Second, as my colleague and I researched youth employment and empowerment, we asked for information and inquired about previous activities and their impacts, we were met with more questions than answers. Members of VIN were pointing at one another to give us the answers. And when we finally got a report or an article, it contained little substance. So, what to do?

Building on our previous university and work experience, we devised a plan to get to the heart of the issue we were tackling. We identified the local stakeholders who might be able to guide us through the circumstances faced by youth in the communities. In the end, we conducted more than twenty interviews. We talked to previous volunteers and VIN-staff, members of the local women’s cooperatives, youth club presidents, teachers, social workers, and ward presidents. We observed events and interactions between young people: in school, at the volleyball field and in the restaurants/kiosks where youth hang out after classes. We attended weddings, teething ceremonies (similar to baptism rituals in Christian cultures), worship and maturation celebrations, joined a charity event and even attended an agricultural fair.

Through this research, the problem became clear:

No education

No jobs

No money

No youth

While conducting these interviews and putting together the puzzle pieces of youth unemployment and migration, we also asked: what workshops would be beneficial for youth empowerment? Why workshops and training? These were the tools we were tasked with to achieve our objectives. But, more importantly, we also felt they were tools our duo—an experienced public speaker and trainer—could use well.

The response was loud and clear: Skills workshops are fine, BUT, IN THE END, WE NEED MONEY.

We could not give the money. So, slightly discouraged but a little less lost, we developed a needs assessment survey, engaging more than 100 young people aged 16-35 in the communities of Taluwa, Thulacchap, and Bhadaure. The 120 questions covered migration patterns, skills and interests, entrepreneurial plans, future aspirations, health and well-being, community involvement, and awareness of VIN.

Among other things, we could clearly identify three different groups of youth whose needs and opportunities significantly differ from one another:

College students

Those in the last two years of high school who still have paths to choose from. What they need is tools and information to be able to make well-informed decisions. Where VIN volunteers can support them best is in improving skills such as English and digital literacy, so that they have better options on the job market locally or elsewhere. In addition, through different game-based activities, they can advance their soft skills, such as critical thinking, teamwork, public speaking, creativity, and time management. But, above all, they need more access to information, opportunities, and a realistic image of the potential profession they want to pursue.

Married women

When marrying, women normally move to the husband’s family; however, we also found that most women stayed within the Okhaldhunga province after marrying. In addition, women often stay behind if their husband migrates elsewhere for better work opportunities. As a result, on the one hand, they manage most of the household work, raising their children and taking care of their animals. On the other hand, many of them are curious to learn new skills! Their primary interest is—not too surprisingly—to improve their agricultural skills, but entrepreneurial skills are a close second. While VIN volunteers can be of little use for the former, many can reliably share business and project management skills!

Returning Migrant Farmers

In fact, they were the hardest to find in the community, as most of them are working in other cities or countries. Almost all the young men we interviewed had worked elsewhere, and many of them were just waiting for their next contract. Some of them picked up work locally. A handful came to the realization that with hard work and a bit of luck, their lives in their home village could be much more meaningful than the ones they had abroad. From our research, we found that they are interested in learning skills such as carpentry, electrical work or driving—skills that put them in a higher pay bracket abroad. From our literature review, we found that there is much more that an NGO or the municipality can do to prepare them for their work abroad and help them in reintegration. These include disseminating information flyers about potential migration destinations, organise workshops to prepare them for their work abroad, organising returnee support groups, and providing individual support with their financial planning before they leave.

We also had the opportunity to test some bite-sized workshop ideas.

Before completing all 100 surveys, we could already identify some trends and gather a basic understanding of our target audience. We did not wait until we could analyse and evaluate all the findings from our surveys. After gathering a basic understanding of the lives and needs of young people, we tested our workshop ideas.

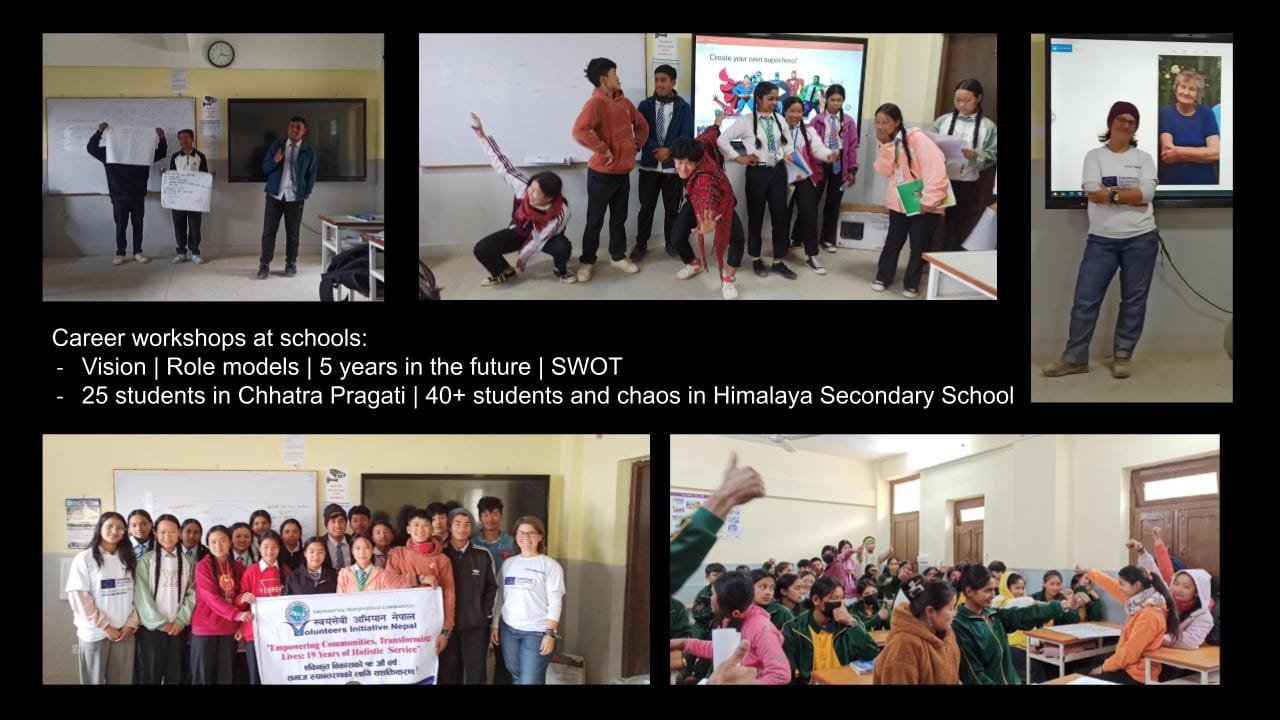

- For college students, we gave a series of mini-sessions focusing on different aspects of career choice: vision and motivation, role models, five years in the future, and SWOT analysis.

- For married women, we offered basic introductory entrepreneurship workshops: vision and SMART goals, 7Ps of marketing, fundraising, and product development. According to some of their feedback, these mini-workshops could be directly translated into practical skills.

- While we did not give workshops specifically targeting the local farmer men, many of them joined our community workshops. These trial workshops had three topics: role models and motivation, mental and physical health, and basic budgeting.

This workshop series was the perfect pilot phase to test some of our ideas and gather positive and encouraging feedback. We sincerely only hope that future volunteers will pick up the work where we left off.

The last sentence:

WE DO WHAT WE CAN!

We received this message in one of the interviews. At the time, it felt like a pitiful acknowledgement of what we were about to do. In my head, at first, it translated to “go ahead with your workshops, since that’s all you can do, but it won’t help anyway.”

However, in the last week of our project, this sentence acquired a deeper meaning. A fellow volunteer found an open grant application for youth empowerment in the Global South, with only 4 days till the submission deadline.

By then, we knew that Nepali people are remarkably flexible, making it possible to come up with project ideas on such a tight deadline.

And that is exactly what we did! We developed and submitted four project ideas, ranging in budget from €500 to €5.000. And it all made sense. The workshop we gave around project goals, the brainstorming techniques we used, and the budgeting we shared—it all made the project proposal possible. And the in-depth observations that made us understand the community’s needs helped us give feedback and fine-tune the project ideas.

So, we did what we could, we did what we do best—and turns out skills workshops are not just nice-to-haves to fill our time. But there are necessary steps to bring money for youth empowerment.

About writer:

Eszter Boros is a trainer, career counsellor and founder, dedicated to guiding individuals through their career transitions. As a passionate hiker, hobby painter, restless traveller, and soon-to-be outdoor educator, she brings a diverse toolkit into her work. This is complemented by her global perspective, Eastern- European self-irony and German precision. At the core of her work are conscious choices, a balanced life, and a connection with nature.